Positive Cardiovascular Health

Following decades of practice and research, doctors, psychologists, and researchers, have noticed conspicuous parallels among the practices and theories of positive psychology, behavioural cardiology, and preventative cardiology. The concepts of positive health and positive psychology emerged when psychologists and clinicians realized that for decades, medical and health-related research has focused entirely on pathology (studying, discovering, and removing the cause and/or symptoms of diseases), and that restoration and maintenance of optimal health is more than merely the absence of its deterioration. In the big picture, researchers have rarely allocated time and resources to studying the positive mental and behavioural landscapes that contribute to a flourishing healthy life worth living.

The links between psychological stress and cardiovascular concerns have been thoroughly established. “Prospective studies consistently indicate that hostility, depression, and anxiety are related to increased risk of coronary heart disease, and cardiovascular death. A sense of hopelessness, in particular, appears to be strongly correlated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Time urgency and impatience … increase the likelihood of developing hypertension. Psychological stress appears to adversely affect autonomic and hormonal homeostasis, resulting in metabolic abnormalities, inflammation, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction.”[1]

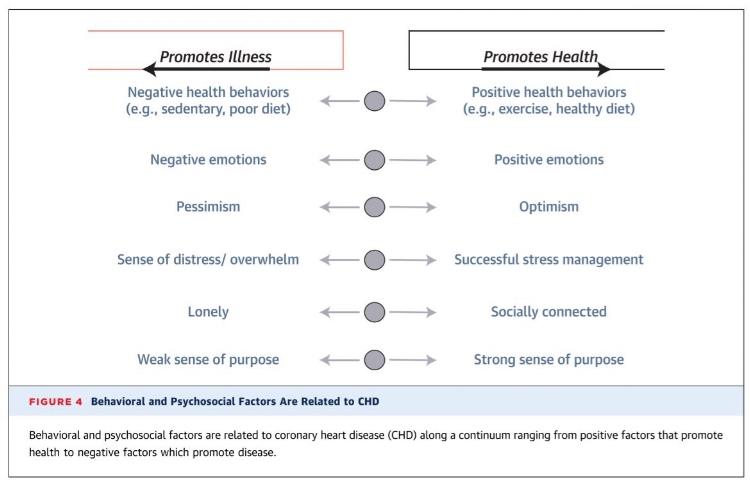

The field of Positive Psychology, in which researchers study and explore optimism, hope, purpose in life, positive emotions, vitality, positive individual traits, psychological well-being, and their effects on physical health appeared at the beginning of the millennium and has been thriving ever since.[2] Psychological well-being is “more than simply the opposite or absence of ill being.”[3] Each psychological and behavioural domain relevant to cardiovascular health (CVH) “exists along a continuum, ranging from positive factors that promote health, to negative factors, which are pathophysiological.”[4] Rozanski illustrates these relevant domains and their spectrums in the following figure. The figure highlights that, for instance, absence of pessimism does not entail optimism. Similarly, lack of negative emotions does not denote the presence of positive emotions.

With the recognition that various lifestyle behaviours, emotional factors, and the experience of chronic stress promote the development and clinical manifestation of coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, and cardiac events, a few years after the appearance of Positive Psychology, the field of Behavioural Cardiology emerged.[5] It has been noted that negative psychological risk factors[6] for cardiac diseases, by their pathophysiological effects, foster negative health behaviours and, together, amplify the risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD).[7] Unhealthy behaviours as a consequence of psychological stress include, “Practical issues like engaging in self-destructive behaviors such as substance abuse, noncompliance with medications, and failure to follow a prudent diet and lifestyle.”[8] Conversely, positive psychological factors, such as optimism and living a purposeful life, cultivate positive physiological states and health behaviours, which in turn, both directly and indirectly promote the prevention of CVDs.[9]

Based on epidemiological data, Rozanski has divided behavioural and psychological risk factors associated with coronary heart disease (CHD) into five categories or domains (A-E in the following table), and elaborates on each of these categories in his paper.[10]

Rozanski considers the separation between behaviour and psychosocial risk factors to be artificial and believes that “Overcoming this divide could lead to the development of more integrated, effective behavioral interventions.”[11] He views this divide as artificial because he notes that the “The risk associated with psychosocial risk factors is generally adjusted for behavioral risk factors, but stimulation of adverse health behaviors is a key causative mechanism by which psychosocial factors increase clinical risk.”[12] To elaborate, he continues, “Just as the use of exercise may help treat psychosocial risk factors, the converse is also true.”[13] There is a “Reciprocal relationship between health behaviors and psychological functioning. For instance, exercise is a health behavior that tends to increase overall health proactivity (eg. better diets), improve sleep, minify the pathophysiological effects of stress, favorably alter brain plasticity and cognitive function, and reduce depressive symptoms.”[14] From the other direction, optimism, a positive psychological factor, results in a greater tendency toward healthy lifestyle habits, such as exercise and better diet.[15] “Studies have found that optimists are more likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors such as eating healthier diets, exercising more, managing stress better, and abstaining from smoking.”[16] Recently a randomized clinical trial revealed that the positive effects of aerobic physical exercise is comparable to the effects of antidepressant medication.[17] It is noteworthy that while aerobic physical exercise has been shown to positively affect cardiovascular health, studies have failed to show reduced mortality and cardiovascular morbidity in response to antidepressants.[18]

By taking into account the artificiality of the psychological-behavioural divide, and by converging positive psychology, behavioural cardiology, and preventative cardiology, the emerging field of Positive Cardiovascular Health provides “A new perspective on how to achieve the goals of promoting, preserving, and restoring CVH at individual and population levels and reducing the population health burden of CVD-related disability, deaths, social disparities, and costs.”[19] This positive approach to cardiology operates on the premise that “The absence of disease does not necessarily translate into the presence of health, just as the absence of depression or other indicators of poor psychological functioning does not guarantee positive psychological functioning,”[20] such as being optimistic and enthusiastic about life. Traditionally, cardiology has been concerned with stopping the degeneration of cardiovascular health, by removing the causes and/or symptoms of CVDs, whereas the positive approach to cardiology studies and promotes restorative biological, cognitive, and behavioural features that promote rejuvenation and maintenance of superior heart health. Processes and features involved in the positive approach to health “Could come into play not only in response to challenge but also during steady states. Periods of healthy functioning may serve as times during which resource capacity is built. Processes involved in building and/or ‘storing’ well-being or health may resemble the mechanism of fat storage in times of food abundance or, in another context, ‘cognitive reserve’ whereby individuals with higher versus lower cognitive capacity are more resistant to neurological disease. Individuals who build such resources may react and adapt to a changing environment more effectively and have the best chance to survive and thrive.”[21]

In what follows, a few selected positive psychological states and behaviours that positively affect cardiovascular health will be stated.

Sense of Purpose

In a recent study, Koizumi et al. reveal that “The risk of mortality from stroke, CVD, and all causes was lower in men with a strong sense of purpose [in life], as compared with men with a low sense of purpose.”[22] They suggest that “The level of the sense of purpose [in life], as a positive perceived factor, is predictive of mortality in men.”[23] Similarly, research in Finland revealed that men, especially alcoholics, who reported satisfaction with life at baseline showed lower mortality than those who reported dissatisfaction with life.[24] The definition of life satisfaction includes not feeling lonely, happiness, interest in life, and general ease of living. Koizume et al. provide a possible explanation for the relationship between having a sense of purpose in life and mortality from CVD. They “Found a higher prevalence of hypertension in men with a low sense of purpose than in men with a strong sense of purpose. Hypertension has been reported to be a risk factor for silent cerebral infarction. Silent cerebral infarction has been related to depression in many studies. Depression is known to increase the risk of mortality from CVD.”[25]

Emotional Vitality

Trudel-Fitzgerald et al. define emotional vitality as “A whole-hearted spirit for life and the ability to regulate emotions.”[26] Their study concludes that “High emotional vitality was associated with reduced hypertension risk,” and positive health behaviours do not entirely explain this relationship.[27] The aim of their study “Was to evaluate the prospective association between psychological well being and incident hypertension in middle-aged men and women.”[28] Their study reveals a “Robust, though small relationship” between emotional vitality and incident hypertension and indicates that “Emotional vitality was protective against hypertension for both younger and older participants, and for both men and women.”[29] Furthermore, emotional vitality has been associated with reduced risk of coronary heart disease[30], as well as reduced risk of diabetes.[31]

Optimism

Optimism, defined as having positive expectancies for the future and/or attaching positive attributions to past events, has been explored frequently to determine its links with cardiovascular health. Kim et al.’s research indicates that optimism predicts a lower risk for heart failure. In their study, a dose-dependent relationship between increasing levels of optimism and decreasing incidences of heart failure was noted. The risk of heart failure in optimists was shown to be approximately half of that in pessimists.[32] In a recent editorial, Rozanski states, “A remarkably consistent recent literature … has linked optimism-pessimism to other cardiovascular outcomes [other than heart failure], including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiac death. In each study in which it has been assessed, a dose-dependent relationship has been observed between increasing optimism and decreasing risk for cardiovascular events. These observations provide conclusive evidence for health benefits of optimism.”[33] [Italics mine] Boehm and Kubzanski share Rozanski’s confidence in that “Across both healthy and patient populations, optimism is the most reliably associated with a reduced risk of cardiac events.”[34]

Happiness

Steptoe and Wardle link happiness to positive biological processes. Following their assessment of various studies, they conclude, “The association between biological responses and happiness are quite robust.”[35] They found an association between happiness and systolic blood pressure. “The association between greater happiness and lower systolic pressure was independent of factors, such as smoking, body mass, and socioeconomic position that are also known to affect pressure levels. It also remained significant after adjustment for negative affect, so was not a reflection of the known relationship between negative affective states and elevated blood pressure.”[36]

Overall Psychological Well-being

Trudel-Fitzgerald et al. illustrate a “possible interrelationship between emotion-related constructs, biological/behavioral pathways, and incident hypertension”[37] in the following graph.

Cognitive reappraisal, “altering emotions to an event by reinterpreting the meaning of the event,”[38] is a positive process in regulating emotions. “It is associated with higher psychological well-being.”[39] On the other hand, expressive suppression, “inhibiting emotional behavior,”[40] is an unhealthy process of regulating emotions, which is “strongly related to higher psychological ill-being.”[41]

Finally, Boehm and Kubzanski, following their comprehensive analysis and review of numerous studies, concluded that “PPWB [Positive Psychological Well-Being] is clearly associated with cardiovascular health, often over and above the effects of ill-being.”[42] “PPWB is inversely associated with deteriorative behaviors and biology,”[43] and it influences cardiovascular health “By directly enhancing behavioral and biological functioning.”[44] Boehm and Kubzanski illustrate their view of the relationship between PPWB and CVD in the following graph.[45][46]

For each of the aforementioned positive psychological and behavioural factors there is plenty of supporting research. In this post, only a few of the stronger studies were highlighted to, first, bring the benefits of a positive approach to health to the forefront of cardiology-related discussions and investigations, and, second, to encourage readers to explore positive cardiovascular health further. This post does not convey the current research on the practical, clinical, and therapeutic interventions and approaches based on the findings of positive psychology and behavioural cardiology. Labarthe et al. convey the common enthusiasm of researchers in this domain by stating, “We believe that, on balance, between substantial supportive research to date and the acknowledged need for further research, the new field of positive cardiovascular health holds great promise and has the potential to develop novel approaches to building CVH at the patient and population levels.”[47] If we are interested in having a healthy heart, which is essential for a healthy life, in addition to learning about what harms the heart, numerous studies consistently show that there are many psychological-behavioural factors that strengthen the heart, which we can acquire and implement in our lives. It is the hope of this author to have sparked the readers’ curiosity regarding this promising field to encourage further exploration and subsequent implementation of positive measures for the wellbeing of the heart. The following illustration[48] may present an effective starting place for further exploration. For every negative psychological and behavioural factor, its counterpart and methods to reach it has been given.

FOOTNOTES & CITATIONS:

[1] Das, Sajal, and James H. O’Keefe. "Behavioral cardiology: recognizing and addressing the profound impact of psychosocial stress on cardiovascular health." Current hypertension reports 10, no. 5 (2008): 374-381. P. 374

[2] Seligman, Martin EP, and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. "Positive psychology: An introduction." In Flow and the foundations of positive psychology, pp. 279-298. Springer Netherlands, 2014.

[3] Trudel-Fitzgerald, Claudia, Julia K. Boehm, Mika Kivimaki, and Laura D. Kubzansky. "Taking the tension out of hypertension: a prospective study of psychological well-being and hypertension." Journal of hypertension 32, no. 6 (2014): 1222. P. 1222

[4] Rozanski, Alan. "Behavioral cardiology: current advances and future directions." Journal of the American College of Cardiology 64, no. 1 (2014): 100-110. P. 100

[5] Rozanski, Alan, James A. Blumenthal, Karina W. Davidson, Patrice G. Saab, and Laura Kubzansky. "The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: the emerging field of behavioral cardiology." Journal of the american college of cardiology 45, no. 5 (2005): 637-651.

[6] A risk factor is a variable associated with an increased risk of disease or infection.

[7] Rozanski, Alan. "Behavioral cardiology: current advances and future directions." Journal of the American College of Cardiology 64, no. 1 (2014): 100-110.

[8] Das, Sajal, and James H. O’Keefe. "Behavioral cardiology: recognizing and addressing the profound impact of psychosocial stress on cardiovascular health." Current hypertension reports 10, no. 5 (2008): 374-381. P. 376

[9] Rozanski, Alan. "Behavioral cardiology: current advances and future directions." Journal of the American College of Cardiology 64, no. 1 (2014): 100-110.

[10] Rozanski, Alan. "Behavioral cardiology: current advances and future directions." Journal of the American College of Cardiology 64, no. 1 (2014): 100-110.

[11] Ibid. P. 105

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Rozanski, Alan. "Optimism and Other Sources of Psychological Well-Being." (2014): 385-387. P. 386

[15] Joutsenniemi, Kaisla, Tommi Härkänen, Maiju Pankakoski, Heimo Langinvainio, Antti S. Mattila, Osmo Saarelma, Jouko Lönnqvist, and Pekka Mustonen. "Confidence in the future, health-related behaviour and psychological distress: results from a web-based cross-sectional study of 101 257 Finns." BMJ open 3, no. 6 (2013): e002397.

[16] Kim, Eric S., Jacqui Smith, and Laura D. Kubzansky. "A prospective study of the association between dispositional optimism and incident heart failure." Circulation: Heart Failure(2014): CIRCHEARTFAILURE-113. P. 398

[17] Blumenthal, James A., Andrew Sherwood, Michael A. Babyak, Lana L. Watkins, Patrick J. Smith, Benson M. Hoffman, C. Virginia F. O'Hayer et al. "Exercise and pharmacological treatment of depressive symptoms in patients with coronary heart disease: results from the UPBEAT (Understanding the Prognostic Benefits of Exercise and Antidepressant Therapy) study." Journal of the American College of Cardiology 60, no. 12 (2012): 1053-1063.

[18] Joynt, Karen E., and Christopher M. O'connor. "Lessons from SADHART, ENRICHD, and other trials." Psychosomatic medicine 67 (2005): S63-S66.

[19] Labarthe, Darwin R., Laura D. Kubzansky, Julia K. Boehm, Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, Jarett D. Berry, and Martin EP Seligman. "Positive cardiovascular health: a timely convergence." Journal of the American College of Cardiology68, no. 8 (2016): 860-867.

[20] Kubzansky, Laura D., Julia K. Boehm, and Suzanne C. Segerstrom. "Positive psychological functioning and the biology of health." Social and Personality Psychology Compass 9, no. 12 (2015): 645-660. P. 645

[21] Kubzansky, Laura D., Julia K. Boehm, and Suzanne C. Segerstrom. "Positive psychological functioning and the biology of health." Social and Personality Psychology Compass 9, no. 12 (2015): 645-660. P. 652

[22] Koizumi, Megumi, Hiroshi Ito, Yoshihiro Kaneko, and Yutaka Motohashi. "Effect of having a sense of purpose in life on the risk of death from cardiovascular diseases." Journal of epidemiology 18, no. 5 (2008): 191-196. P. 193

[23] Ibid.

[24] Koivumaa-Honkanen, Heli, Risto Honkanen, Heimo Viinamäki, Kauko Heikkilä, Jaakko Kaprio, and Markku Koskenvuo. "Self-reported life satisfaction and 20-year mortality in healthy Finnish adults." American Journal of Epidemiology 152, no. 10 (2000): 983-991.

[25] Koizumi, Megumi, Hiroshi Ito, Yoshihiro Kaneko, and Yutaka Motohashi. "Effect of having a sense of purpose in life on the risk of death from cardiovascular diseases." Journal of epidemiology 18, no. 5 (2008): 191-196. P. 195

[26] Trudel-Fitzgerald, Claudia, Julia K. Boehm, Mika Kivimaki, and Laura D. Kubzansky. "Taking the tension out of hypertension: a prospective study of psychological well-being and hypertension." Journal of hypertension 32, no. 6 (2014): 1222.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid., P. 1225

[29] Ibid., P. 1226

[30] Kubzansky, Laura D., and Rebecca C. Thurston. "Emotional vitality and incident coronary heart disease: benefits of healthy psychological functioning." Archives of General Psychiatry 64, no. 12 (2007): 1393-1401.

[31] Boehm, Julia K., Claudia Trudel-Fitzgerald, Mika Kivimaki, and Laura D. Kubzansky. "The prospective association between positive psychological well-being and diabetes." Health Psychol 34, no. 10 (2015): 1013-1021.

[32] Kim, Eric S., Jacqui Smith, and Laura D. Kubzansky. "A prospective study of the association between dispositional optimism and incident heart failure." Circulation: Heart Failure(2014): CIRCHEARTFAILURE-113.

[33] Rozanski, Alan. "Optimism and Other Sources of Psychological Well-Being." (2014): 385-387. P. 385

[34] Boehm, Julia K., and Laura D. Kubzansky. "The heart's content: the association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health." Psychological bulletin 138, no. 4 (2012): 655. P. 677

[35] Steptoe, Andrew, and Jane Wardle. "Positive affect and biological function in everyday life." Neurobiology of Aging 26, no. 1 (2005): 108-112. P. 111

[36] Ibid.

[37] Trudel-Fitzgerald, Claudia, Paola Gilsanz, Murray A. Mittleman, and Laura D. Kubzansky. "Dysregulated blood pressure: can regulating emotions help?." Current hypertension reports 17, no. 12 (2015): 92.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Boehm, Julia K., and Laura D. Kubzansky. "The heart's content: the association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health." Psychological bulletin 138, no. 4 (2012): 655. P. 684

[43] Ibid., P. 682

[44] Ibid.

[45] Hedonic well-being denotes “Subjective well-being, which includes both cognitive and affective evaluations of one’s life as a whole.” Eudaimonic well-being denotes having “Having life purpose” and “A life worth living.”

[46] Boehm, Julia K., and Laura D. Kubzansky. "The heart's content: the association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health." Psychological bulletin 138, no. 4 (2012): 655. P. 659

[47] Labarthe, Darwin R., Laura D. Kubzansky, Julia K. Boehm, Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, Jarett D. Berry, and Martin EP Seligman. "Positive cardiovascular health: a timely convergence." Journal of the American College of Cardiology68, no. 8 (2016): 860-867. P. 866

[48] Rozanski, Alan. "Behavioral cardiology: current advances and future directions." Journal of the American College of Cardiology 64, no. 1 (2014): 100-110.